- An agreement by 190 governments last December at the United Nations biodiversity conference in Montreal highlights the role of companies and investors in conserving nature and ecosystems.

- The pact could incentivize private investment in conservation, boost pressure on companies to reduce pollution, and energize efforts to require companies and investors to publish their nature-related impacts.

- The agreement also adds to growing pressure on companies and investors to eliminate commodity-driven deforestation.

A landmark agreement reached last December at the United Nations (U.N.) biodiversity conference (COP15) has put the spotlight on how nature can be preserved using, in part, the priorities and disclosures of companies and investors.

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), as the COP15 agreement is known, aims to protect 30% of the planet’s land and water by 2030 and phase out subsidies that harm nature. The agreement calls for all countries that ratified it to map out national action plans that could, among other steps, introduce regulations requiring companies and investors to publish their nature-related risks, dependencies and impacts.1

More broadly, the GBF and its targets could serve as a road map for investors and other capital-markets participants to address biodiversity loss. In this blog post, we look at issues shaping the analysis of nature-related financial risk and key takeaways from the GBF for investors, as well as offer a snapshot of related regulation and standard setting.

Why biodiversity matters for investors

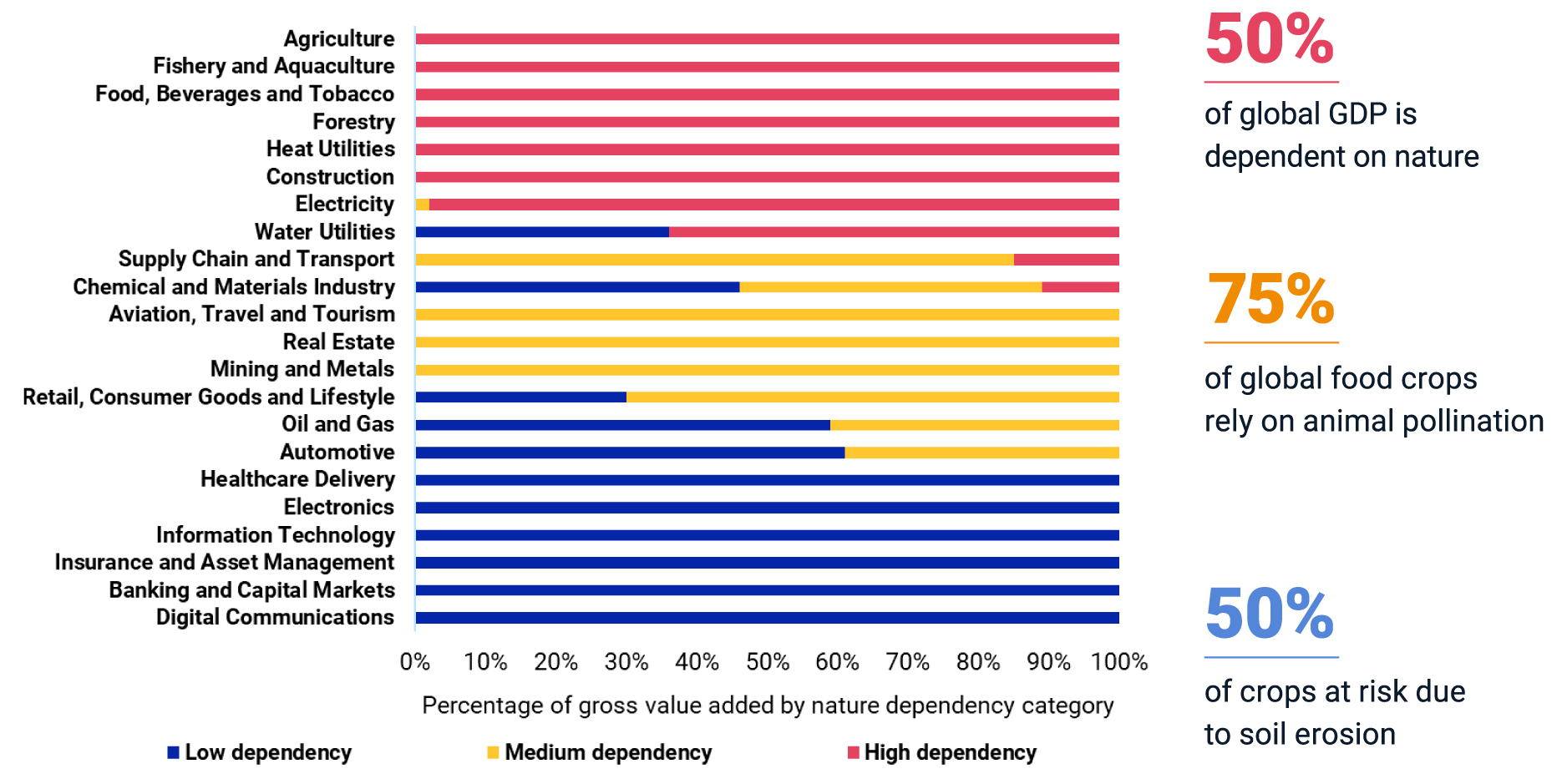

More than half of the world’s economic output is either highly or moderately dependent on intact ecosystems and their benefits, which include food and timber, climate control, soil formation, water and air purification and pollination.2

Earth’s biological diversity ensures that these natural processes function. Yet both biodiversity and ecosystems are dwindling at an unprecedented rate. Three-quarters of terrestrial ecosystems and two-thirds of the oceans have been negatively affected by human activities, according to the U.N. intergovernmental scientific platform on biodiversity.3 A quarter of existing animals and plant species could face extinction.4 The destruction of natural habitats, overharvesting of resources, pollution, a changing climate and the introduction of invasive species all fuel biodiversity loss.5

Dependencies of industries on natural capital

Source: IPBES, MSCI ESG Research, World Economic Forum and PwC

Climate change can exacerbate other contributors to biodiversity loss, while biodiversity loss worsens the impacts of climate change. Forests, wetlands and oceans absorb an estimated 60% of annual global human-caused greenhouse-gas emissions.6 Intact ecosystems such as forests and floodplains protect against consequences of climate change such as flooding and soil erosion. As we lose nature, we lose our ability to combat climate change too.

Key provisions of the GBF

The GBF lays out four overarching goals for conserving and restoring biodiversity and natural ecosystems by 2050 and 23 specific targets for action this decade.7 Here are three areas of note for investors.

Finance. The GBF could lead to more development aid as well as blended capital earmarked for conservation. It aims to mobilize at least USD 200 billion a year globally for conservation by 2030 from both public and private sources, with the goal of reaching USD 700 billion a year by midcentury. The mechanism envisions countries receiving compensation for designating biodiversity-rich areas for protection.

Pollution reduction. The GBF calls for farmland, fisheries and forests to be managed sustainably and for countries to reduce pollution and its negative impacts from all sources this decade to levels not harmful to biodiversity. The provisions could increase pressure on the agriculture, chemicals, mining or oil and gas industries, for example, to develop more overarching programs for toxic-waste management and disposal.

Select GBF provisions of significance for companies and investors

Source: Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework

Regulation and disclosure. The GBF calls for multinational companies and financial institutions to measure and report their biodiversity-related risks, dependencies and impacts, including throughout their operations, supply and value chains, and investment portfolios, as well as for companies to supply consumers with information to promote sustainable consumption.

Though the GBF leaves to national regulators the specifics of such disclosures, emerging frameworks in Europe and the U.S. echo this directive. The European Union (EU) is developing extensive biodiversity-related reporting requirements, consistent with its 2030 biodiversity strategy.8 The framework proposes to establish a common classification of economic activities that contribute to protecting and restoring biodiversity and ecosystems, and to take steps to ensure the financial system contributes to reducing biodiversity risk.9

Other countries are following suit. In France, for example, Article 29 of the Energy-Climate Law directs financial firms to publish the main biodiversity-related risks arising from their investments.10 In the U.S., climate-related disclosure rules proposed by the Securities and Exchange Commission would direct companies that have set targets related to conservation or the restoration of ecosystems to publish such targets and how they intend to meet them.11

The EU also leads in terms of ambition and scope when it comes to reducing deforestation.12 Companies that want to keep selling into the bloc must ensure their supply chains do not include certain goods and commodities produced on land anywhere in the world that was deforested after 2020.13

Overview of key regulations on deforestation-free products

Source: MSCI ESG Research

Our research finds both significant exposure and gaps in preparedness for companies. Our analysis flagged 11% of MSCI ACWI Index constituents as having the potential for direct or indirect contribution to deforestation, as of Nov. 30, 2022.14 While 94% of food producers and 86% of food retailers were flagged for direct or indirect contribution to deforestation, only 12% and 18%, respectively, had adopted a basic policy on forest loss.15

The GBF is also likely to energize efforts to standardize reporting of nature-related financial risk. The Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures aims to complete a voluntary reporting framework modeled on the Task Force for Climate-related Financial Disclosures this September. It is among a series of initiatives designed to help investors measure and report on nature-related risks and engage companies on biodiversity.16 The International Sustainability Standards Board has said it will make nature-related risk part of a disclosure framework it is developing.17

A final word of caution

While the GBF reflects high ambition, only time will tell if its targets will be achieved. Its predecessor, a set of biodiversity targets for 2020 that the Convention on Biodiversity agreed to a decade earlier, were not.18 Several aspects of the GBF, including its emphasis on implementation and a focus on substantially boosting conservation funding from both public and private sources, differentiate the agreement from that earlier effort. Negotiators also hope that a review of countries’ action strategies and plans slated for COP16 in 2024 will facilitate the latest effort to protect biodiversity where previous ones failed.19

1“Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.” Convention on Biological Diversity, Dec. 18, 2022. The U.S. is not officially a party to the GBF but participated in negotiating its terms.

2“Ecosystem Goods and Services.” European Commission, September 2009.

3“Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.” Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), May 6, 2019.

4Ibid.

5Ibid.

6Ibid.

7“Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.”

8“EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030.” European Commission, May 20, 2020

9“Draft European Sustainability Reporting Standards, ESRS E4 – Biodiversity and Ecosystems.” European Financial Reporting Advisory Group, November 2022.

10“Publication of the implementing decree of Article 29 of the Energy-Climate Law on non-financial reporting by market players.” Ministry of Economics, Finance and Industrial and Digital Sovereignty, June 18, 2021.

11“The Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors,” Securities and Exchange Commission, March 21, 2022.

12“Climate change: new rules for companies to help limit global deforestation.” European Parliament. Sept. 13, 2022.

13“Deal on new law to ensure products causing deforestation are not sold in the EU.” European Parliament, Dec. 6, 2022.

14Arne Philipp Klug. “Deforestation Risks on the Rise.” MSCI ESG Research, Dec. 14, 2022.

15Based on MSCI ACWI Index constituents. Industry and sector classifications are based on the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS®), the industry-classification standard jointly developed by MSCI and S&P Global Market Intelligence.

16See, for example: “At COP15, investors announce Nature Action 100 to tackle nature loss and biodiversity decline.” Nature Action 100, Dec. 11, 2022.

17“ISSB describes the concept of sustainability and its articulation with financial value creation, and announces plans to advance work on natural ecosystems and just transition.” ISSB, Dec. 14, 2022.

18“Global Biodiversity Outlook 5.” Convention on Biological Diversity, Aug. 18, 2020.

19“Mechanism for planning, monitoring, reporting and review.” Convention on Biological Diversity, Dec. 18, 2022.

Further Reading

Deforestation Risks on the Rise

Biodiversity: The New Frontier of Sustainable Finance

Location Matters: Using Geospatial Analysis to Assess Biodiversity Risks