- As natural hazards and climate-change risks increasingly materialize, quantifying sovereign bonds’ physical and transition risk may help investors determine the climate resiliency of their portfolios.

- Major fossil-fuel producers largely comprise the bottom quartile of countries for the MSCI Climate Change and Natural Hazards Risk Factor Score due to a combination of physical and transition risks.

- Investors can use this information to not only identify sovereign-bond issuers with higher climate-related risk but determine where investments may create the most impact.

Climate change is a major risk for sovereign credit.1 Hurricane María, the displacing floods of Pakistan2 and enormous bushfires in Australia3 are all examples of natural hazards that have had a significant macroeconomic impact. For that reason, measuring a country’s exposure to and management of both the physical and transition risks of climate change is becoming an increasingly important consideration for sovereign-debt investors.

The MSCI Climate Change and Natural Hazards Risk Factor Score may help guide the analysis of these complex risks. The score includes assessments of exposure and management of physical and transition risks for the 198 countries rated under the MSCI ESG Government Ratings methodology. Investors can use this information to assess the extent to which countries are exposed to physical and transition risks and how well these risks are being managed. The score could also help identify which countries might be on a path toward mitigating and adapting to these risks.

Worst performers tend to be major fossil-fuel producers

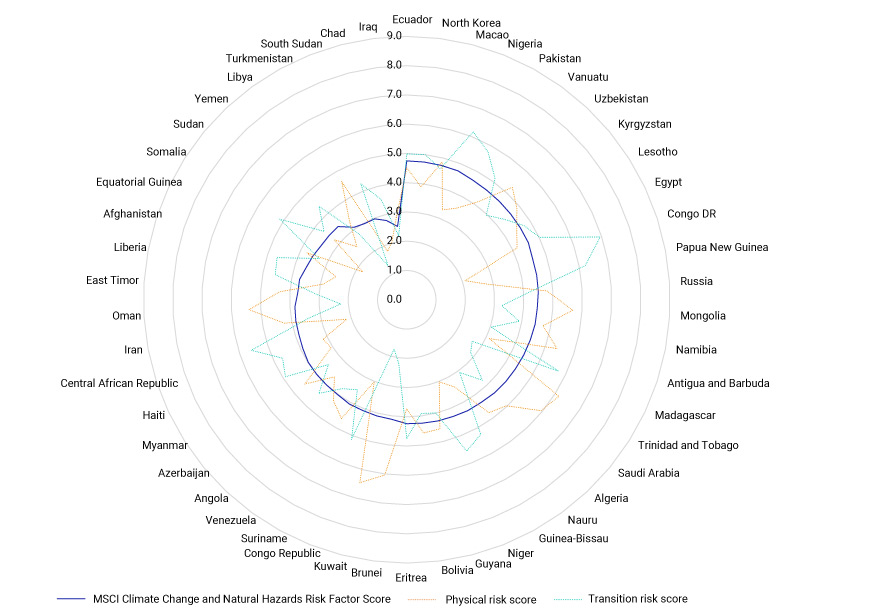

Countries with low MSCI Climate Change and Natural Hazards Risk Factor Scores have tended to have high exposure to physical and transition risks, lack the management mechanisms needed to cope with these risks, or some combination of the two.

Most major fossil-fuel producers in our universe were ranked in the bottom quartile of the risk-factor distribution as of June 2023, with the exceptions of the U.S., Norway, Bahrain, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. Within this quartile, there were also several African and Caribbean nations. While they are not fossil-fuel producers, they face substantial climate-change and natural-hazard risks.

Half of the countries in the bottom quartile scored worse on transition risk than on physical risk. This was the case for sovereigns such as Kuwait, Oman and Turkmenistan, which were exposed to three factors that dominate our assessment of transition risk: high greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions, hydrocarbon rents and fossil-fuel subsidies.

Conversely, the countries more susceptible to physical risks may be vulnerable not only to acute climate change and natural hazards, which can materialize instantly, but to the chronic physical risks and the forward-looking socioeconomic implications of climate change. Furthermore, the bottom-quartile sample scored poorly in physical risk management. In other words, these countries may struggle with the institutional and infrastructure quality needed to mitigate and adapt to physical risks. This is important because strong risk management can help address risk vulnerability. Japan, which had high physical-risk exposure yet robust management, is a positive example of this.

An even split between physical and transition risks in the bottom quartile

Risk factor and sub-factor scores for bottom quartile of the universe, highest score of the quartile starting with Ecuador then descending clockwise (n=50). Data as of June 8, 2023. Source: MSCI ESG Research

Many climate-vulnerable countries may need greater technical and financial assistance

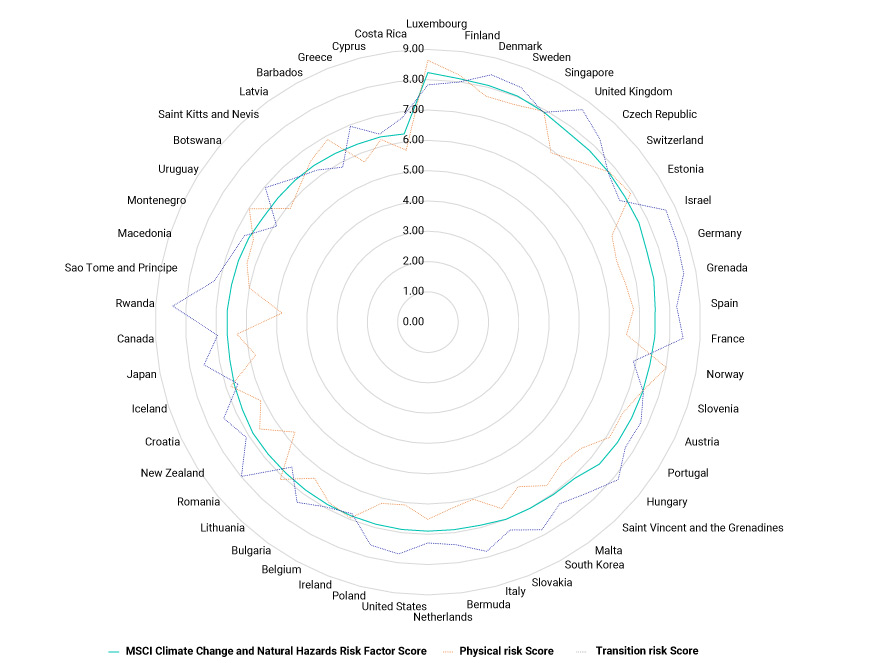

Investors can refer to the top quartile of the MSCI Climate Change and Natural Hazards Risk Factor Scores to not only identify those countries with the lowest physical and transition risks, but understand how they became leaders in climate resiliency and adaptation. These nations typically possess robust institutions and sturdy infrastructure to confront physical risks when they materialize. They also spend lower sums of money on hydrocarbon subsidies, have decreasing GHG-intensity trajectories and trade higher amounts of low-carbon-technology products, which may suggest lower transition risks.

Investors could also use this kind of analysis in discussions with governments about climate-risk exposure and management. Such dialogue could include sharing technical expertise as well as nuanced advice on building consensus with domestic stakeholders and may also help inform countries’ climate action plans. Multilateral bodies such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) could also assist with these discussions.

Top performers could offer guidance on physical- and transition-risk resiliency

Risk factor and sub-factor scores for top quartile of the universe, highest score starting with Luxembourg then descending clockwise (n=50). Data as of June 8, 2023. Source: MSCI ESG Research

A role for impact investors?

While investor engagement with governments could help inform countries’ climate action plans, additional investment may be needed. Without significant investment, climate-vulnerable nations could potentially face greater risks in the future.4 Many countries that scored in the bottom quartile of the MSCI Climate Change and Natural Hazards Risk Factor Scores may struggle to tap international capital markets, with the notable exception of Persian Gulf states, which possess the capital to invest in projects that would mitigate physical and transition risks.

For instance, USD-denominated sovereign bonds for Pakistan, Ecuador, Bolivia and Egypt all had option-adjusted spreads of more than 1,000 basis points as of June 2023,5 which makes it difficult, if not impossible, to raise hard currency for public financing. Venezuela defaulted on its sovereign debt in November 2017, as did Suriname in April 2021. As of June 2023, Venezuela remained in default while Suriname reached a restructuring deal with bondholders in May 2023,6 though it remained in default on some of its private, bilateral debt. Most of this group of countries would therefore need to raise money on local markets, seek bilateral aid or loans or turn to a multilateral institution such as the IMF7 to generate cash.

Impact investors could play a role by identifying sovereign-bond issuers where their marginal dollar could go furthest. Even though the investable universe for this group of countries is still limited, these investors may jockey for bilateral private financing, participate in emerging mechanisms such as debt-for-nature swaps8 or purchase local-currency bonds if their mandates allow it.

1Serhan Cevik and João Tovar Jales. “This Changes Everything: Climate Shocks and Sovereign Bonds.” International Monetary Fund, June 5, 2020.

2“Pakistan: Flood Damages and Economic Losses Over USD 30 billion and Reconstruction Needs Over USD 16 billion – New Assessment.” The World Bank, Oct. 28, 2022.

3“Ten Impacts of the Australian Bushfires.” United Nations Environment Programme, Jan. 22, 2020.

4Vera Songwe et al. “Financing for Climate Action: Scaling up Investment for Climate and Development.” London School of Economics, Nov. 8, 2022. Songwe et al. argue that emerging and developing countries alone need USD 1 trillion per year to finance advancements in “net zero, adaptation, resilience and natural capital.”

5The bonds used for this analysis include Pakistan (PKGV 7.375 04/08/2031), Ecuador (ECGV 2.5 07/31/2035), Suriname (SRGV 9.25 10/26/2026), Bolivia (BOGV 7.5 03/02/2030) and Egypt (EGGV 7.3 09/30/2033). Data from Refinitiv Eikon.

6Rodrigo Campos, Jorgelina Do Rosario and Ana Kuipers. “Exclusive: Suriname Reaches Debt Restructuring Deal with Bondholders.” Reuters, May 4, 2023.

7The IMF has a new financing program called the Resilience and Sustainability Facility (RSF), which provides financing to “strengthen economic resilience and sustainability.” The RSF would require policy reforms to boost climate-change preparedness.

8Rodrigo Campos and Marc Jones. “Ecuador Frees Cash for Galapagos Conservation with $1.6 Billion Bond Buyback.” Reuters, May 5, 2023.

Further Reading

How Climate Transition Risk May Impact Sovereign Bond Yields