In May 2024, the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) released its Guidelines on funds’ names using ESG or sustainability-related terms (“Guidelines”).[1] As of Nov. 21, 2024, these Guidelines will apply to all newly-launched funds and, six months later, to all existing funds. These new rules will have a notable impact — in previous research, we estimated that roughly 32% or EUR 2 trillion of self-labeled Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) Article 8 and 9 funds could be affected. Many fund managers will need to either change their fund names or exclude certain constituents.

Setting the scene

A key requirement of the Guidelines is that specific companies need to be excluded, depending on what a fund chooses to name itself. Exclusion criteria are derived from the EU’s Paris-Aligned Benchmark (PAB) and Climate Transition Benchmark (CTB) categories, as defined in Article 12(1) of the Commission Delegated Regulation (CDR).[2] CTB criteria apply to “transition,” “social” and “governance” terms and require screening for activities related to tobacco and controversial weapons, or to violations of universal social norms. The PAB criteria are more extensive and not only encompass the CTB criteria but also set thresholds for revenue from fossil-fuel-related business activities and apply to any reference to terms such as “sustainable,” “green,” “impact,” “ESG” or “environmental” in a fund name.

ESMA isn’t the first regulator to have applied the PAB exclusion criteria. The European Banking Authority (EBA) has also referenced them in binding standards on Pillar 3 disclosures of ESG risk for banks to assess exposure to fossil-fuel-based activities.[3] And while these exclusion criteria have already been functioning within the climate benchmarks context, their application within the context of the Guidelines may prove challenging.

It’s harder than it looks

Identifying companies based on their revenues from specific business activities may sound simple enough, but the reality is a lot more complicated. Companies do report revenue segments, but often not to the required level of detail. Estimations, interpolations and assumptions are often the only way to match revenue to specific activities, which still leaves challenges to overcome. Identifying the right approach also depends on what the end user needs.

Fossil-fuel-based sub-set of PAB criteria and implementation challenges

| Criteria | Implementation challenge |

|---|---|

| Companies that derive 1% or more of their revenues from exploration, mining, extraction, distribution or refining of hard coal and lignite. | Revenue from coal production (or extraction) can largely be captured from company disclosures. However, revenue from the distribution or refining of coal remains elusive due to limited reporting. |

| Companies that derive 10% or more of their revenues from the exploration, extraction, distribution or refining of oil fuels. Companies that derive 50% or more of their revenues from the exploration, extraction, manufacturing or distribution of gaseous fuels. |

Where companies report separate volumes of oil and gas produced and do not aggregate as “barrels of oil equivalent,” oil and gas revenue can be separated. However, for value chain activities, this can be more challenging. For example, not all pipeline companies disclose a bifurcation between the revenue they generate for oil versus gas. |

| Companies that derive 50% or more of their revenues from electricity generation with a greenhouse gas (GHG) intensity of more than 100g CO2e/kWh. |

Individual power plant emissions and production data are largely unavailable, hindering the use of production intensities consistently across power-generation companies. It is possible to use average production intensities based on GHG emissions across all operations and electricity generation, but this can lead to overestimations of the intensity ratio in the case of diversified utilities or where power generation is not 100% of a company’s operations. |

Table is based on ESMA fund-name guidelines, as detailed in endnote 2. Source: MSCI ESG Research

Erring on the side of caution

The Guidelines aim to address greenwashing risks for retail investors. Where precise, detailed company disclosures are missing, fund managers may opt for a more cautious approach (i.e., more exclusions, rather than fewer) to meet regulatory expectations. Taking such conservative approach, we selected a single (10%) revenue threshold for oil-and-gas-related activities that includes equipment and services companies for the MSCI ESMA PAB screen. For funds using sustainability- or ESG-related terms in their names, this threshold would exclude 627 of 8,702 constituents of the MSCI ACWI Investable Market Index (IMI), or 10.6% of the index by weight.

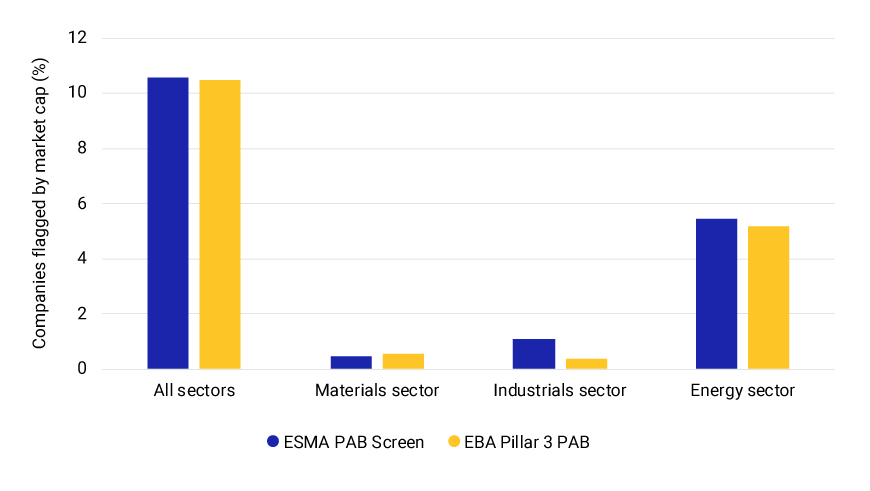

By contrast, in our experience, banks reporting their fossil-fuel exposures as part of the EBA’s Pillar 3 risk disclosure requirements are not as sensitive about their indirect exposures. In such a scenario, one option would be to apply the 50% revenue threshold for gas-related activities but leaving out equipment and services providers. This would exclude 475 companies (10.48% by weight) — fewer than in our ESMA PAB screen. Under both approaches, however, energy is the most affected sector, as shown below.[3]

As fossil-fuel-related regulatory compliance needs continue to expand, we are working to enhance our revenue-estimation models and granularity. Better disclosures that make it possible to separate activities along the fossil-fuel value chain will enable more fine-grained precision in the application of exclusion criteria (oil vs. gas).

Different approaches to PAB criteria trigger different exclusions

The road ahead

The CTB and PAB exclusion criteria may have been originally designed for benchmark indexes, but in practice they are often referenced by regulators. Last year, the market was consulted on the potential EU sustainability labels for funds and these could be more comprehensive, potentially building on adverse-impact indicators from the EU SFDR. However, any potential changes will not be introduced overnight.

In the meantime, sustainability-minded fund managers may face a difficult choice between fund naming and preferred investment strategy. In earlier research, we found that only 68% of sustainability-named Article 9 funds excluded fossil fuels. More granular tools to screen out unwanted assets may help fund managers overcome this dilemma and support their dialogue with regulators.

This information is provided “as is” and does not constitute legal advice or any binding interpretation. Any approach to comply with legal, regulatory or policy initiatives should be discussed with your own legal counsel and/or the relevant competent authority, as needed.