The latest earnings season has already contained a number of high-profile surprises, such as Facebook’s beat after the market close on Jan. 30, which drove a 10.82% jump in the stock the following day.1 We noted that some of the surprises were actually part of a long streak of surprises, and generally in the same direction (consecutives beats or misses). This observation led us to ask whether there is persistence to earnings surprises — or more generally, to ask what information past earnings surprises have provided about the likelihood of future surprises, and how the market has responded.

We show below that, historically, there has been persistence in earnings surprises: Companies that had reported a beat (or miss) in the prior quarter or quarters more often reported a surprise in the current quarter — and in the same direction. In addition, a company’s likelihood of reporting another surprise in the same direction increased as the length of the streak increased. Finally, we found that the market response was larger when a streak came to an end.

We should only be surprised by the fact that we’re surprised

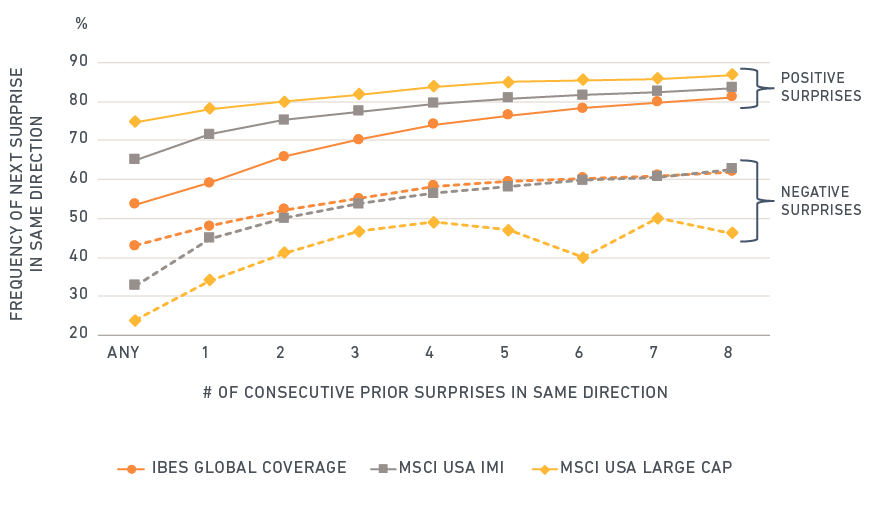

The exhibit below shows the frequency of positive and negative quarterly-earnings surprises in three different universes: IBES Global Coverage, the MSCI USA IMI and the MSCI USA Large Cap Index. While the trend of companies with a streak of earnings beats or misses being more likely to continue surprising in that direction applied to all three, the frequency of positive surprises was larger in the U.S. than elsewhere, and even higher among U.S. large-cap stocks.2

Earnings surprises have tended to be followed by further earnings surprises in the same direction

Source: Thomson Reuters IBES, MSCI Research. Values are averages from Q1 of 2002 to Q3 of 2018. Surprise is defined as the difference between reported actual earnings and the IBES consensus estimate on the reporting date. Only companies reporting quarterly earnings were considered for this analysis.

How the market has reacted to true surprises

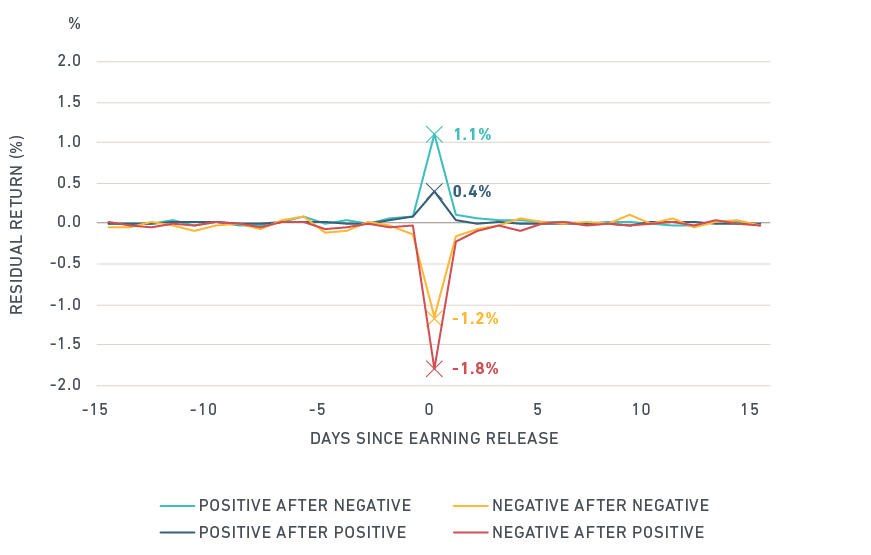

We also investigated the stock-price response to an individual earnings surprise, conditional on past surprises. The exhibit below shows the average residual return (the return after accounting for the effects from the market, industries, styles and all other factors) from the Barra US Total Market Equity Trading Model around the earnings-release date for four groups of stocks. The stocks are sorted based on the sign of their latest and prior earnings surprises.

We found that earnings that surprised in the opposite direction of the previous quarter’s surprise generated a larger stock-price response than surprises in the same direction — in other words, when the surprise was truly a surprise. And companies that reported a positive surprise following a negative surprise generated a return on release more than twice that of those that reported two consecutive positive surprises.

Stock prices have had greater movement when a quarterly-earnings surprise reversed direction

Source: Thomson Reuters IBES, MSCI Research. Values are averages from Q1 of 2002 to Q3 of 2018 for U.S. large-cap stocks. For companies that announce earnings before market close, Day 0 represents the return from the previous day to the announcement day’s close. For companies that announce after market close, Day 0 represents the return from announcement day to the next day’s close.

Earnings surprises in motion have tended to stay in motion

Analyzing the history of earnings surprises showed the odds have been in favor of a positive- or negative-surprise streak’s continuing, and that the market has reacted strongly when a streak has ended.

1 Yahoo Finance Facebook Inc. share price quote

2 Due to the rapidly decreasing sample size of companies with long strings of negative surprises in the MSCI USA Large Cap Index universe, we saw some deviation from the general trend as we increased the number of prior surprises.

Further Reading

Is there a short interest factor?

Is there an options sentiment factor?

Equity markets in November – Do pro-cyclical risks remain?

Creating a common language for factor investing