- Companies’ governance practices can have a significant impact on how — and how effectively — investors engage with climate laggards to push for better net-zero alignment.

- The Climate Action 100+ engagement focus companies had a higher proportion of widely held companies than the MSCI ACWI Index, but most companies in the focus group nevertheless have a controlling or principal owner that could reduce engagement’s effectiveness.

- Only 20% of the Climate Action 100+ focus companies have annual director elections with binding majority voting. For the rest, investors’ ability to hold directors accountable for climate performance may be weaker.

Investors can decarbonize their portfolios by tilting toward companies with low and improving emissions, but the ultimate goal of net-zero investing is to reduce emissions of greenhouse gas in the real world — not just within a portfolio. This may mean engaging with climate laggards, such as companies that have yet to set credible or sufficiently ambitious net-zero targets. By communicating net-zero climate expectations and holding companies accountable when climate performance falls short, investors can push for a convergent net-zero pathway where laggards eventually catch up to net-zero leaders.

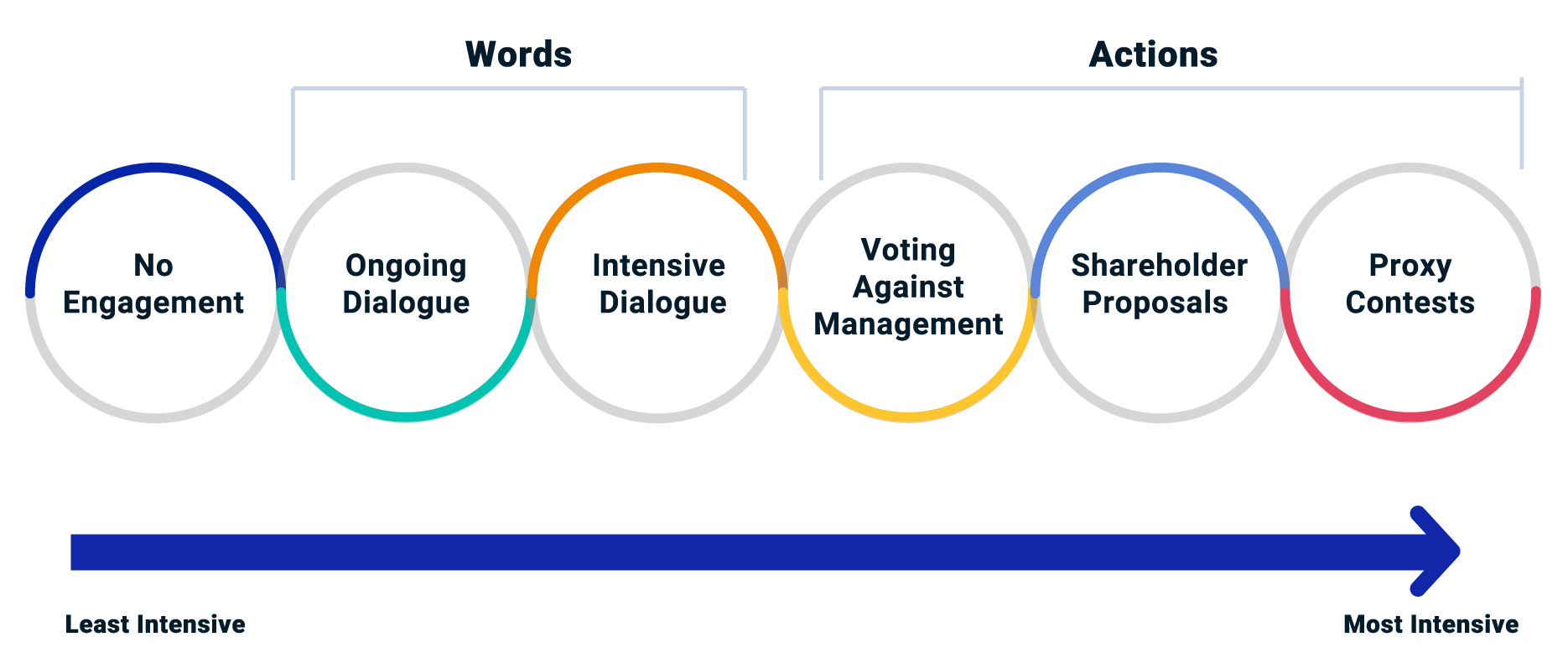

A firm’s governance structure determines which engagement tools are available to investors. By evaluating governance practices, investors can determine which of the tools highlighted below may be most effective at influencing a company’s behavior. These include informal mechanisms that rely on words and formal governance mechanisms that rely on actions.

Mechanisms for investor engagement

Source: MSCI ESG Research LLC.

The investor-led initiative Climate Action 100+ has targeted 166 companies for engagement due to their globally significant GHG emissions and strategic importance to the global carbon transition.1 We analyzed the governance practices of these focus-group companies to understand the engagement challenges and opportunities investors may face when pushing for decarbonization pathways aligned with portfolio targets.2

The exhibit below looks at the frequency among the Climate Action 100+ companies of five governance factors that can have an impact on the effectiveness of investor engagement.

Corporate governance at Climate Action 100+ focus companies

Source: Climate Action 100+, MSCI ESG Research.

In the remainder of this post, we discuss how governance factors can influence engagement.

Ownership, control and engagement

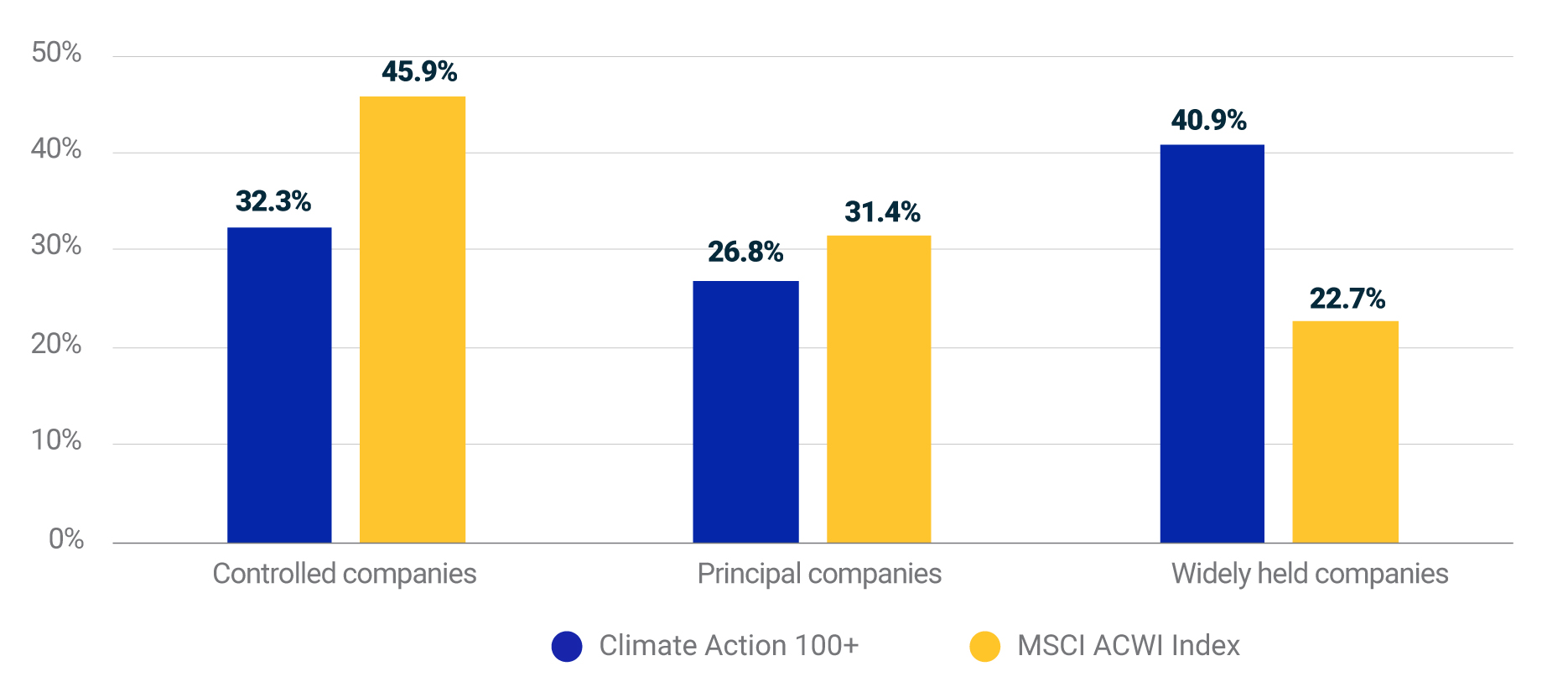

Understanding a company’s ownership structure is key to understanding its broader governance framework. One important dimension is the company’s level of control. We classify companies as being:

- Widely held: No shareholder controls more than 10% of votes.

- Principal: The largest shareholder or bloc controls 10% to 30% of votes.

- Controlled: The largest shareholder or bloc controls 30% or more of votes.

As shown in the exhibit below, widely held companies were nearly twice as prevalent within the Climate Action 100+ focus group than within the broader MSCI ACWI Index.

Ownership classification of Climate Action 100+ companies by region

As of Sept. 8, 2022. Source: Climate Action 100+, MSCI ESG Research.

Widespread ownership may benefit investors. Formal engagement mechanisms — for example, voting against a management proposal or submitting a shareholder proposal — are more likely to succeed when there is no large, insider-aligned voting bloc ready to quash a challenge from other investors. If ownership is highly dispersed among many investors, however, shareholders may struggle to overcome inertia and marshal enough votes to challenge the status quo.

For controlled companies — and principal companies, where the largest owner is insider-aligned — formal engagement mechanisms are less likely to succeed. For the nearly 60% of Climate Action 100+ companies that are controlled or principal-owned, investors may need to focus on dialogue to effect change on climate. This is especially true for companies that deviate from a “one-share, one-vote” capital structure, as minority investors may find their influence reduced at the expense of a major shareholder.

Dialogue can be escalated by bringing private conversations into the public forum — for example, by publishing an open letter or speaking at the company’s annual general meeting. And, even when they fail, formal engagement mechanisms that win significant support from minority investors can send a powerful message and potentially lead to reputational costs for companies.3

Holding boards accountable

Opposing a director’s reelection is a powerful way to express concern about a company’s net-zero ambitions, but investors may wish to consider their vote’s potential impact — or lack thereof.

We put director-election regimes into three categories:

- Plurality voting: The directors who receive the most votes will be elected. This means all nominees are guaranteed to be elected in an uncontested election.

- Plurality voting with resignation policy: A plurality election, but directors must resign if they don’t get majority support (the board can usually choose to reject the resignation and keep the director).

- Majority voting: Directors are elected only if they get majority support. Directors who do not receive majority support will automatically leave the board.

Votes against directors are most impactful under majority voting regimes because — in sufficient numbers — those votes carry the promise of removal from the board.

Another important factor is how often directors stand for election. In some markets, they typically do so annually (e.g., in the U.K. and Canada and at most U.S. companies). In others, directors serve multiyear terms and stand for election every few years (e.g., Australia and France).

Nearly half (49%) of Climate Action 100+ companies have majority voting in director elections, and most (63%) provide for the annual election of all directors, but only one-fifth (20%) provide for both.

At companies that do not provide for annual director elections, dissatisfied shareholders may have to carefully consider the most appropriate directors to hold accountable in a given year — particularly for those few companies that also use majority voting. Where elections are not conducted via majority voting, investors may find their ability to effect change by voting against directors diminished.

So far, Climate Action 100+ supporters appear to have voted against directors rarely, possibly because it is a very confrontational tool. The vast majority of directors at Climate Action 100+ focus-group companies received strong support from shareholders in 2022. Only a third of companies (34%) saw a director receive less than 90% support, and none saw a director receive less than majority support. It remains to be seen whether more investors will employ this tool.

Strengthening net-zero strategies

Ownership structures and election regimes for board members are just two of the governance factors we discuss in our paper on net-zero engagement. Other factors that can influence engagement success include how potential engagement targets are identified and prioritized, how climate performance is evaluated, the identities of key owners and the voting options available to shareholders. Bigger picture, the question for investors is whether they are willing to engage with high-carbon-emitting companies and, if so, what tools they’re prepared to use.

1“Companies.” Climate Action 100+.

2All analysis in this blog post used our latest available data and research as of Sept. 8, 2022. Our analysis included 164 of the 166 total Climate Action 100+ focus-group companies, excluding one company that had been acquired and one that was not in MSCI ESG Ratings coverage.

3Kastiel, Kobi. 2016. “Against All Odds: Hedge Fund Activism in Controlled Companies.” Columbia Business Law Review 2016(1): 60-153.

Further Reading

Net-zero Alignment: Engaging with Companies

Constructing Net-Zero Portfolios: Three Approaches

Implementing Net-Zero: A Guide for Asset Owners

Ownership and Control 2022: Global Equities Concentration on the Rise