This blog post originally appeared on Burgiss.com. MSCI acquired The Burgiss Group, LLC in October 2023.

Private-capital investors are currently facing two types of climate risks: physical and transition. Physical risks result from extreme climate events, such as floods, wildfires, heatwaves and hurricanes, that cause financial losses. Transition risks arise from moving toward a carbon-constrained economy, driven by changes in climate policies, cheaper low-carbon technologies, and a shift in consumer and investor sentiment toward green solutions.[1]

Measuring climate-transition risks as well as conducting climate stress tests are increasingly gaining momentum, as worries mount over the risk of stranded assets and the uncertainty around their long-term valuations. For instance, the Bank of England has indicated that if government policies were to change globally in accord with the Paris Agreement, two-thirds of the known global fossil-fuel reserves would not be burned, which would lead to changes in the value of fossil fuel investments.[2]

This blog post serves as an introductory piece for a research series that will estimate climate-transition risks of private companies and examine how their profitability could be impacted by various carbon-pricing schemes. The first step is to map the financial materiality of GHG emissions to private companies in order to estimate their carbon exposures. This post covers U.S. portfolio companies, held by buyout funds.

Emissions are not created equal

Calculating climate-transition risks requires an understanding of the financial materiality of GHG emissions in private companies and the consequent exposures to climate regulatory risks. Financial materiality can be understood as the relevance of a specific ESG factor to a company’s financial performance, business model and enterprise value. For example, GHG emissions can be relevant and financially material to carbon-intensive companies due to the growing regulatory restrictions and the associated compliance costs.

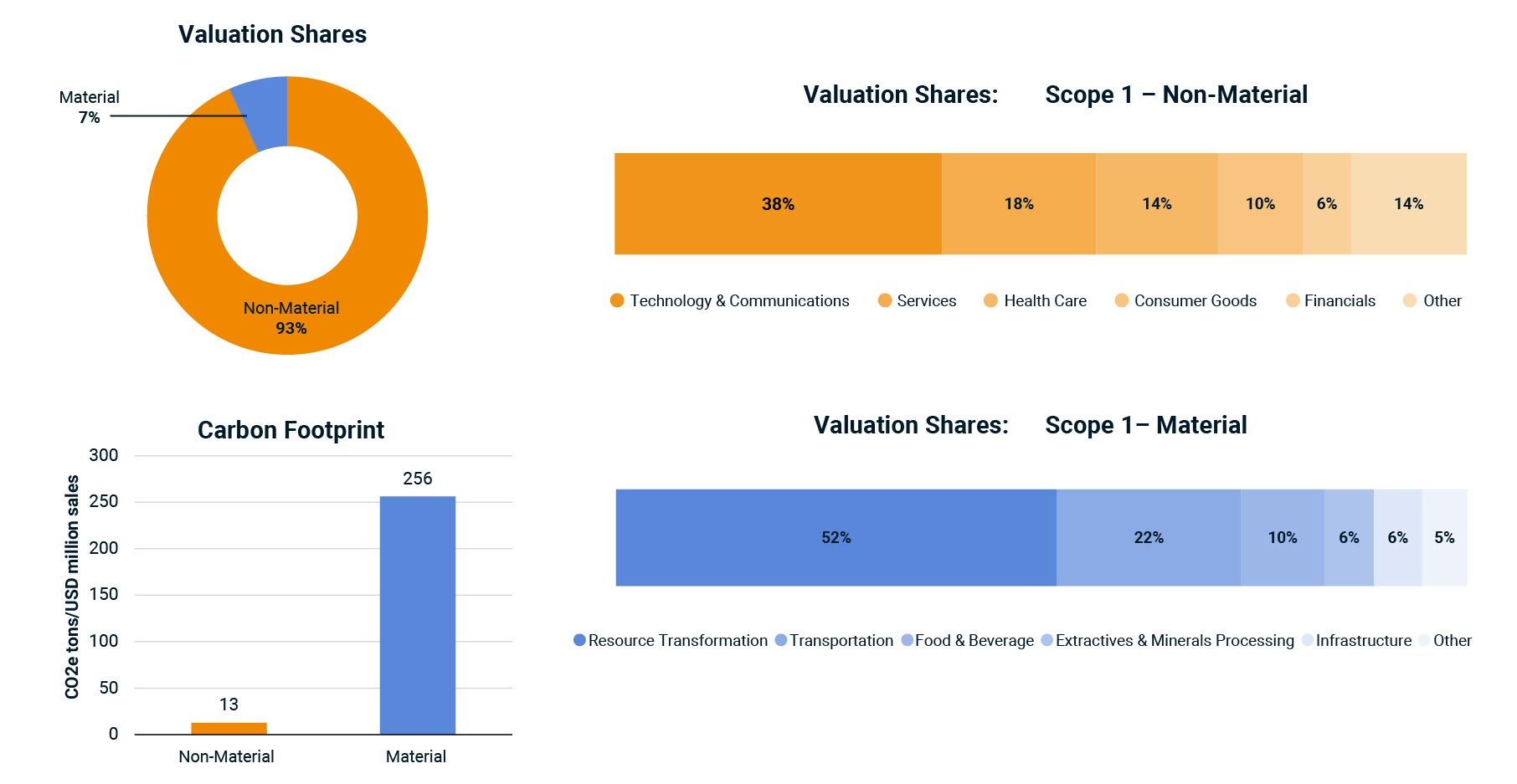

Using the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) Standards, the Burgiss data universe of private companies is divided into “material” and “non-material” segments based on the financial materiality of their direct GHG emissions (Scope 1).[3] These two samples are expected to be fundamentally different in terms of their carbon footprints, climate regulatory exposures, and climate-transition risks. Burgiss has mapped over 120,000 private portfolio companies and properties from the Burgiss Manager Universe (BMU) to the SASB Standards, allowing limited partners (LPs) to detect opportunities and risks in their portfolios.

The exhibit shows that GHG emissions are estimated to be financially material to only 7% of the buyout funds’ aggregate U.S. holdings valuation, or to 10% of the underlying U.S. private portfolio companies, by count. The “material” subset is relatively small but has a Scope 1 carbon-intensity estimate of about 256 tonnes CO2/USD sales, or over 20 times the non-material subset’s average, demonstrating a significant exposure to climate policy.[4] Identifying the material subset (10% of company count) will allow LPs to effectively monitor and engage with general partners (GPs) on this concentrated part of their portfolios and the associated carbon footprint and climate-regulatory risks.

SASB GHG emission materiality: climate vulnerabilities within buyout funds

Looking ahead

While private markets are inherently opaque with minimal climate disclosure, LPs’ growing engagements with GPs and portfolio companies could prove valuable in expanding climate transparency. Prioritizing climate-disclosure engagements with companies that face financially material climate transition and regulatory risks may be valuable in risk management and mitigation.

The next posts in this series will examine climate-transition risks across private companies and estimate the impact of various carbon-price scenarios on profitability, using upstream and downstream approaches.