- Climate change is an important component of an ESG ratings model, but an ESG rating is not a climate metric.

- By design, weights vary based on their financial relevance to specific sectors. So MSCI ESG Ratings for oil and gas companies, cement makers and electric utilities have substantial weights on climate risks and opportunities.

- Carbon emissions are highly correlated with E-pillar scores where they are financially relevant, and they bear little correlation where they are not financially material.

ESG ratings have become widely used in both active management and ESG indexes, with a growing focus on climate change. This has led to increasing debate about two intertwined questions: First, why are ESG ratings of companies so different across providers? And second, how do ESG ratings reflect climate risk?

What ESG Ratings Measure

It’s true that ESG ratings from different providers are not well correlated. Recent academic studies have found correlation levels of around 0.4 to 0.5 — much lower than the 0.9 commonly found for credit ratings from various rating agencies.1 But comparing ESG ratings to credit ratings misunderstands what they are trying to do. Put simply, all credit ratings measure the same objective (assessing the ability of debtors’ ability to meet their obligations), while different ESG ratings may measure different objectives. What’s more, ESG ratings measure varying things, from environmental (e.g., toxic emissions and green buildings) to social (e.g., labor management) to governance (e.g., ownership and business ethics). Climate change is an important component of an ESG ratings model, but an ESG rating is not a climate metric.

At a very high level, ESG methodologies may attempt to address either or both of the following two questions: 1) How well does a company manage environmental, social and governance risks that could affect its enterprise value? (This is what MSCI ESG Ratings are designed to do.) 2) Is a company “good” for society and the environment? (I.e., does it have a positive or negative social impact, regardless of whether that impact is relevant to investors?) Other providers’ ESG ratings may focus more on this second question, or on a mix of the two. (MSCI ESG Research provides other models and datasets focused on this second question.)

How MSCI ESG Ratings Reflect Climate-Change Risks and Opportunities

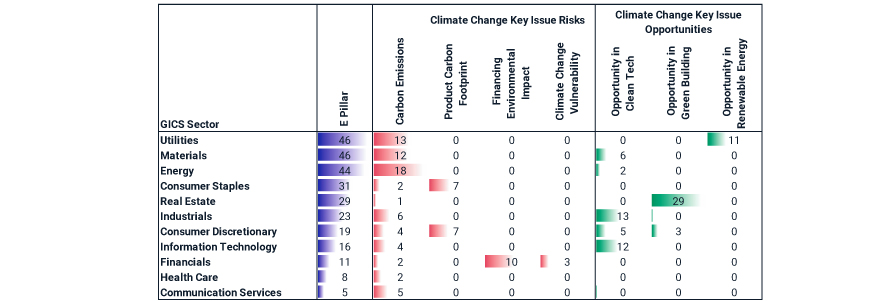

The MSCI ESG Ratings model consists of 35 possible key issues. In each Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS®)2 sub-industry, the most financially relevant of these are identified and used to calculate the rating, with the four governance key issues included for all companies. The exhibit below shows the average weight within each sector given to the E-pillar score and each individual climate-risk and climate-opportunity key-issue score within the MSCI ESG Ratings methodology. (Key issues within the E pillar also include things like water stress and toxic emissions and waste. For simplicity, these are not shown in the table below.)

Average Weight of E-Pillar and Climate-Change Key-Issue Scores in the MSCI ESG Ratings Methodology

Data as of Sept. 30, 2021. Source: MSCI ESG Research LLC

The key point here is that, by design, weights vary based on their financial relevance to specific sectors. So ESG ratings for oil and gas companies, cement makers and electric utilities have substantial weights on climate risks and opportunities, especially carbon emissions (which they emit a lot of) and opportunities in clean technology and renewables (where they could be part of the solutions to climate change). In contrast, real estate developers don’t emit a lot of carbon directly, but whether or not they are dealing in green buildings is starting to define their future prospects. For banks, their biggest climate risk lies in what they finance, so that’s what is weighted more heavily in the model. And since telecoms face only limited climate-transition risk, this sector isn’t highly weighted (unlike, for example, privacy and data security).

In industries where climate risk is not heavily weighted, a company may see its ESG rating actually improve even if its carbon emissions are increasing. That could occur if, for example, its (more heavily weighted) non-climate-related metrics are improving or if its emissions grow more slowly than in the rest of the industry.

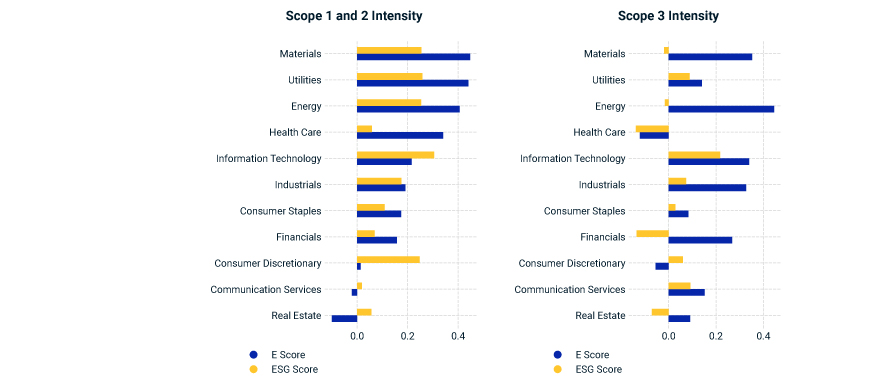

Also by design, how much carbon an individual company emits is highly correlated with E-pillar scores in sectors where climate risk is financially relevant, but bears little correlation where it isn’t. To understand how this works, it is important to distinguish between Scope 1+2 emissions (operational) and Scope 3 emissions (upstream or downstream — e.g., emissions from companies financed, for banks, or from cars on the road, for automakers).

As shown in the exhibit below, within the most carbon-intensive sectors (materials, utilities and energy), there was a strong correlation between operational carbon efficiency (Scope 1+2) and the E-pillar score. So, for example, the oil and gas producers with the lowest emissions per unit of revenue had the highest scores. But for telecommunication services, there is virtually no relationship, because their Scope 1+2 emissions are limited and so are their transition risks.

When we turn to Scope 3 emissions efficiency, the strongest relationships between that metric and E-pillar scores were in sectors where Scope 3 issues are the most financially relevant (those weighted more heavily in the exhibit above). The energy sector comes up again because of opportunities to rein in downstream emissions (from fuels being used) by offering renewables, for information technology it’s about making things like solar panels or climate-modeling software.

Carbon Efficiency, ESG Ratings and the E-Pillar Score: Emissions Correlations by Sector

MSCI ACWI Investable Market Index, as of Sept. 30, 2021. ESG Scores are the numerical scores that underly the letter ratings.

As would be expected, higher MSCI ESG Ratings were also well correlated with better carbon efficiency for the sectors where climate-change risks and opportunities are highly financially relevant; while for the sectors where these are less relevant and the issues not as heavily weighted, there was a weaker relationship between carbon-emissions profile and the final rating.

1Berg, Florian, Kölbel, Julian, and Rigobon, Roberto. “Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings.” MIT Sloan School of Management Working Paper, Aug. 15, 2019.

Christensen, Dane, Serafeim, George, and Sikochi, Anywhere. “Why is Corporate Virtue in the Eye of the Beholder? The Case of ESG Ratings.” The Accounting Review, Feb. 26, 2021.

Dimson, Elroy, Marsh, Paul, and Staunton, Mike. 2020. “Divergent ESG Ratings.” Journal of Portfolio Management, 47: 75-87.

LaBella, Michael J., Russell, Joshua, and Novikov, Dimitry. “The Devil is in the Details: The Divergence in ESG Data And Implications for Responsible Investing.” QS Investors, September 2019.

2GICS is the global industry classification standard developed by MSCI and S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Further Reading

ESG Ratings: How the Weighting Scheme Affected Performance

Which ESG Issues Mattered Most? Defining Event and Erosion Risks